In memory of Mario Segre, Noemi Cingoli, Marco Segre

23/05/1944 - 23/05/2024

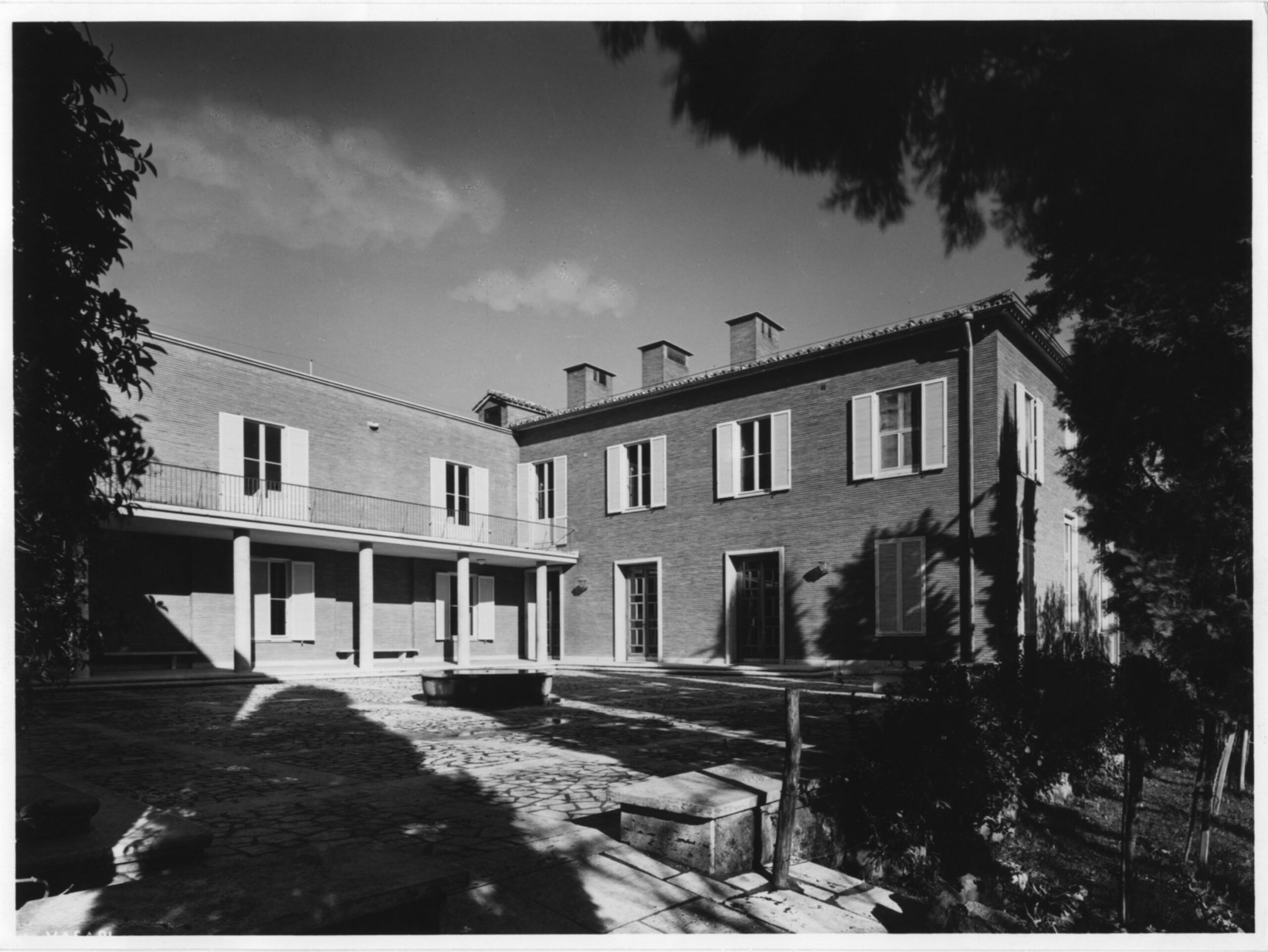

The Swedish Institute, a refuge for the Segre family

Mario Segre with his wife Noemi Cingoli and their son Marco escaped the round-up on 16 October 1943, during which Mario’s mother Ida Luzzati and sister Elena were arrested, deported to Auschwitz and killed.

Mario, Noemi and Marco found refuge at the Swedish Institute of Classical Studies, where they were let in by the director Erik Sjöqvist. According to Axel Gauffin’s account, Mario Segre had turned up at the Institute’s gate early one morning; the family had left their home before dawn and so as not to arouse suspicion, the three had separated. Shortly afterwards, Noemi also arrived with little Marco.

Sjöqvist made a courageous choice, on a personal basis: «I overstepped my authority, but for humanitarian reasons», he stated in 1945.

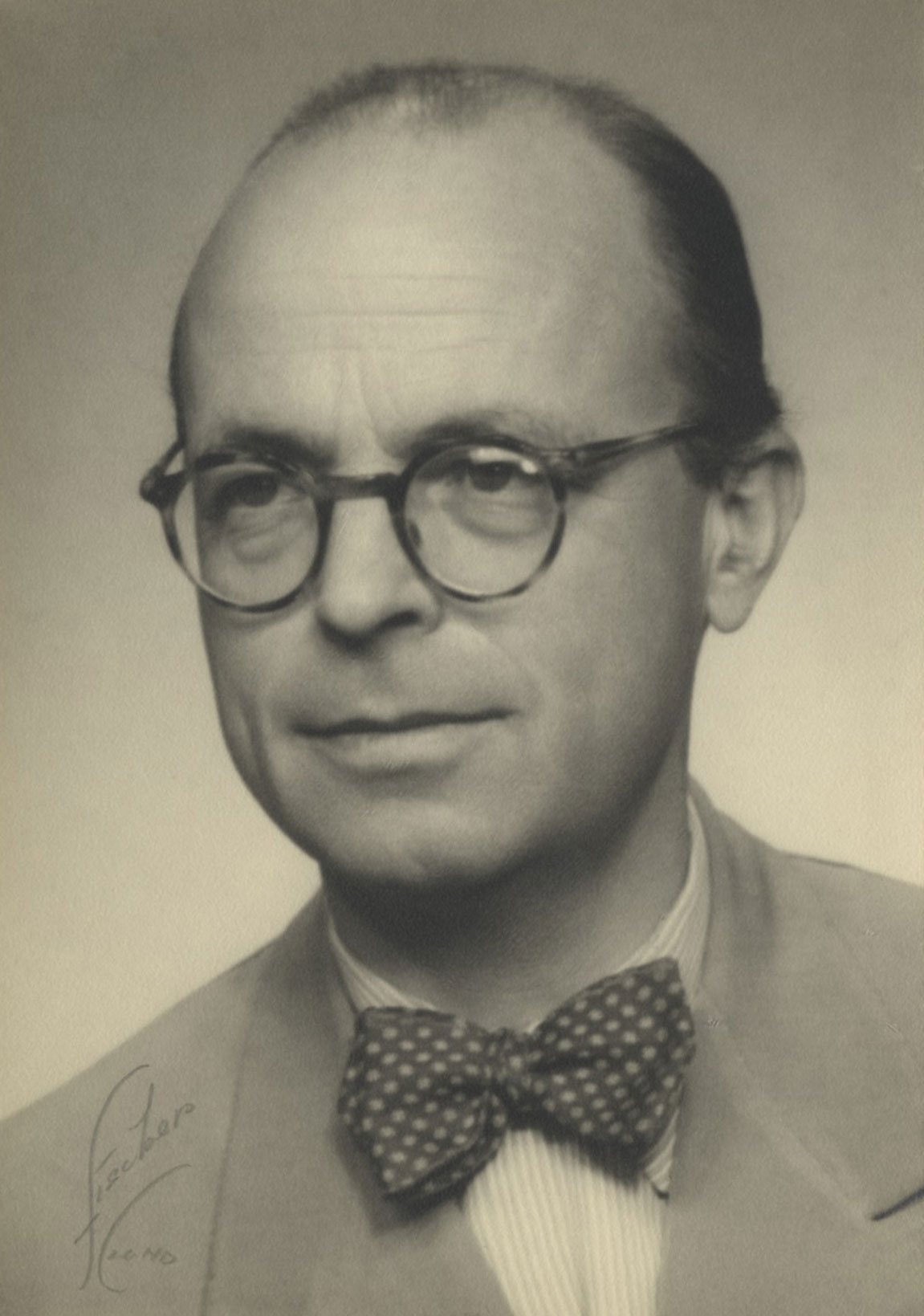

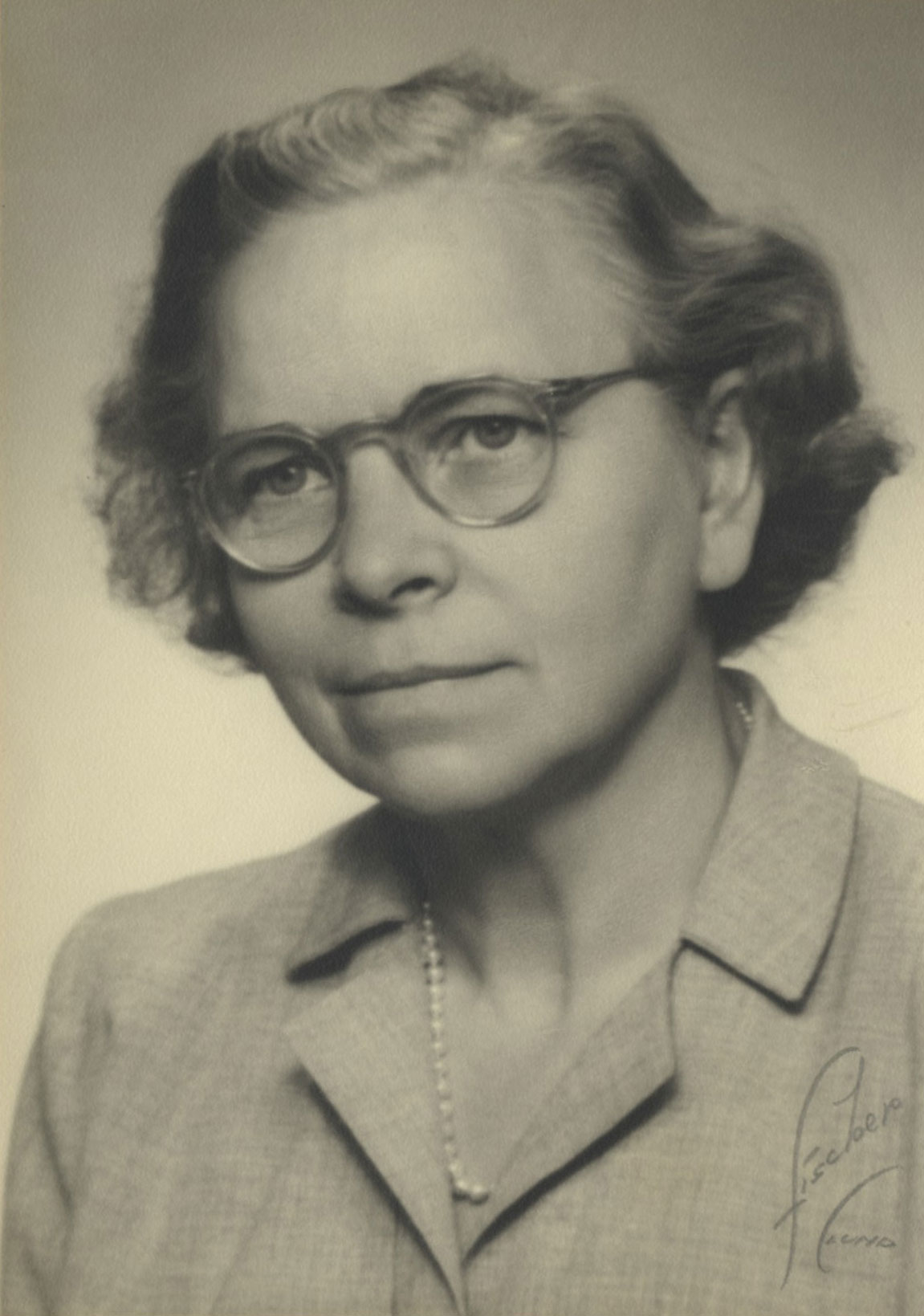

Erik and Gurli Sjöqvist

Erik Sjöqvist (1903-1975) studied classical archaeology at the University of Uppsala under Axel W. Persson and participated in the Swedish excavations of Asine in 1926 and Dendra in 1927. Between 1927 and 1931 he took part in the Swedish Cyprus expedition under the direction of Einar Gjerstad.

In 1940 he was appointed director of the Swedish Institute of Classical Studies in Rome; the Institute, founded in 1925, had just moved to new premises in via Omero, designed by architect Ivar Tengbom. In 1941, Sjöqvist married Gurli Wallbom (1894-1984), who had lived in Rome since the 1920s and worked at the Swedish legation.

During the difficult years of the war, Sjöqvist, as a representative of a neutral nation and thanks to his extraordinary human qualities, played a leading role in the international community in Rome and the Institute became a point of reference for scholars who remained in the city. Thanks to his commitment, the International Union of Institutes of Archaeology, History and Art History in Rome and the International Association of Classical Archaeology were founded after the war. In 1948, at the end of his tenure as director of the Institute, Sjöqvist served as adviser to the Swedish Crown Prince, and later King, Gustaf VI Adolf; he was later offered the chair of Classical Archaeology at Princeton University and from 1955 he directed the archaeological excavations at the site of Morgantina in Sicily.

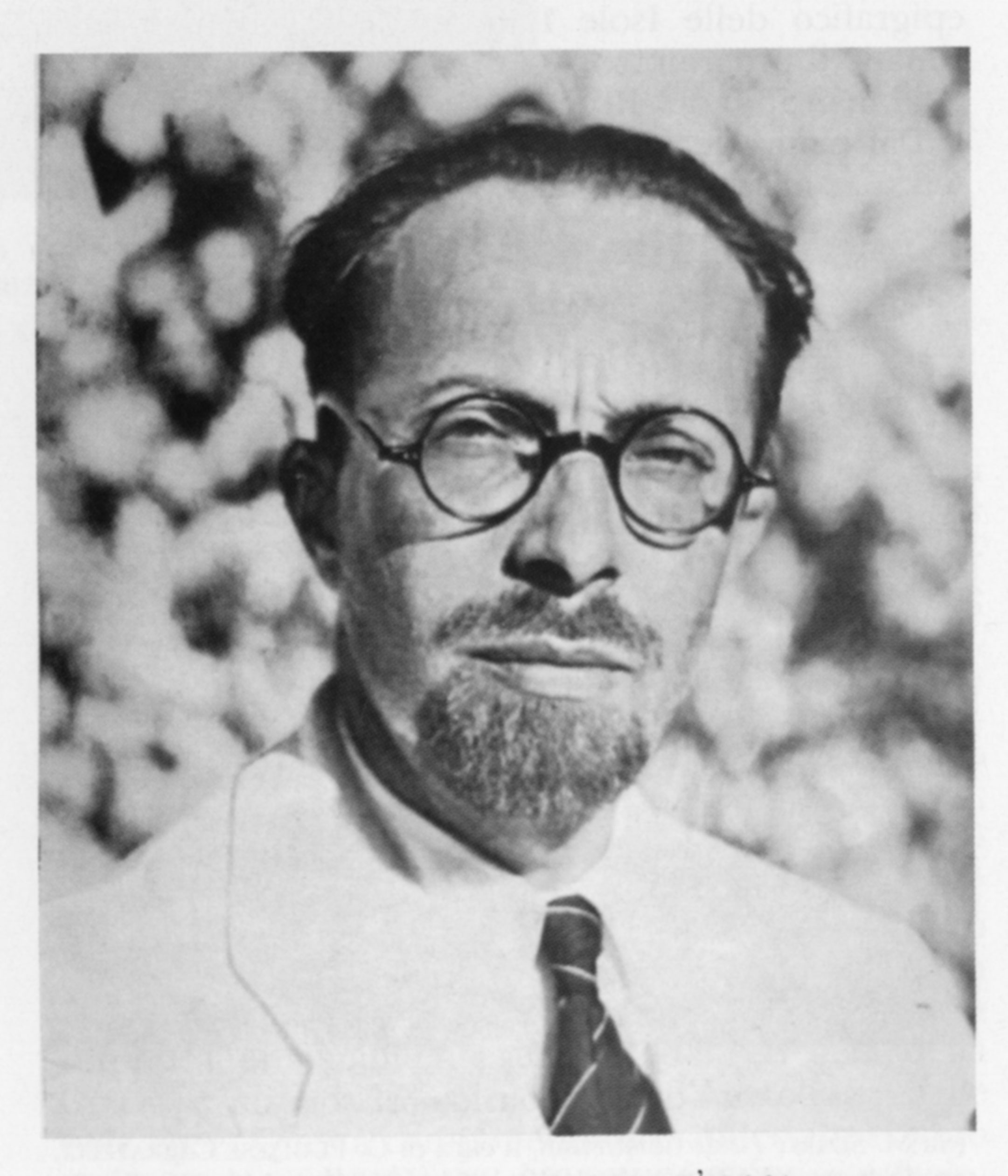

Mario Segre,

a brilliant scholar

Mario Segre was born in Turin on 16 October 1904, the first of four children of Giuseppe Segre and Ida Luzzati. After graduating in literature in 1926 from the University of Genoa, he taught Latin and Greek in several high schools in northern Italy.

Parallel to his role as a teacher, in 1930 he obtained a scholarship at the Italian Archaeological School at Athens and in the following years a number of scholarships at FERT in Rhodes, an important cultural foundation in the Dodecanese islands.

In 1934, Segre was awarded a professorship in Epigraphy and Greek Antiquities at the University of Milan, and in 1936 he was released from teaching in order to devote himself to research at the Royal Institute of Archaeology and History of Art in Rome; in the same year he was entrusted with the task of compiling the Corpus of Inscriptions of the Italian Aegean Islands. These were intense years of study and travel in the Dodecanese, where he stayed for a long time between 1930 and 1940.

His scholarly activity, which ranged from epigraphy to the history of the Hellenistic-Roman period, resulted in numerous articles published in prestigious journals, thanks to which he received great recognition.

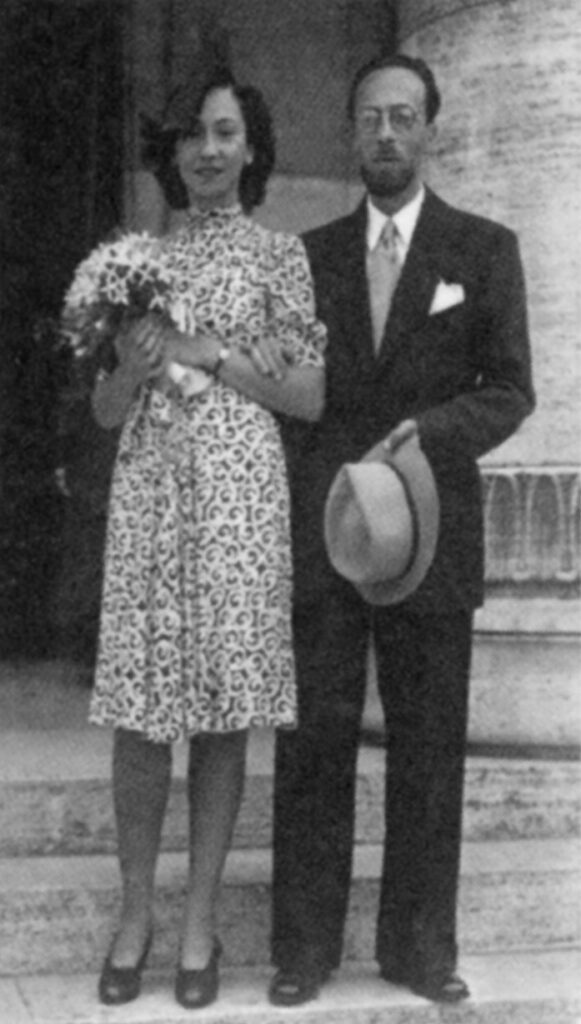

The racial laws, the meeting and marriage with Noemi Cingoli

From September 1938, with the promulgation of the fascist racial laws, Mario Segre’s intense research, study and teaching activities came to an abrupt halt: he was dismissed and expelled from all activities and institutions and forced to retire at only 34 years of age. After a few vain attempts to get a job or a scholarship abroad, he was forced, in June 1940, to leave the Aegean, which he never saw again.

Back in Italy, he settled in Rome, where his mother and sister had been living for a few years. Here he had met Noemi Cingoli, born on 25 September 1913, the youngest of four children of Alfredo Cingoli and Clelia Ravà. Noemi had attended the art school in via di Ripetta. Mario and Noemi were married on 7 September 1941.

Between mid-1940 and January 1942, Mario moved between Rome and Milan in search of work opportunities. In addition to giving private lessons, he was able, thanks to Gaetano De Sanctis, to write some entries for the Treccani’s Enciclopedia minore, which were signed by archaeologist Luisa Banti. Mario tenaciously continued to dedicate himself to his studies and in particular to the epigraphical Corpus, being able to count on the support of Giovanni Pugliese Carratelli and Renato Bartoccini. His work was made difficult as he was gradually denied access to libraries. In 1940 he was prevented from attending the library of the German Archaeological Institute following the denunciation of the archaeologist Giulio Jacopi.

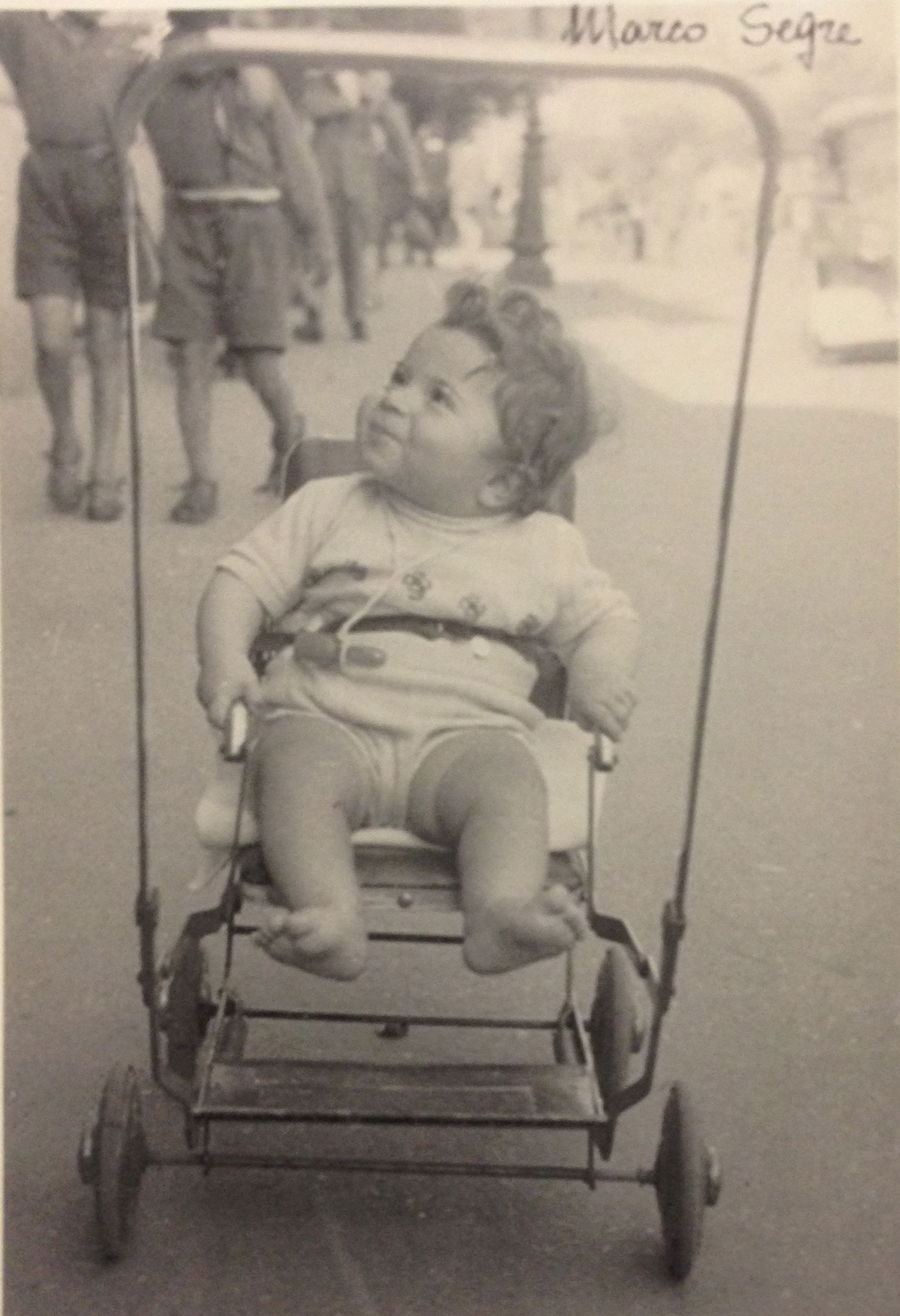

On 1 June 1942, their son Marco was born in Milan and in mid-December the family returned permanently to Rome. With the fall of the fascist government and the Nazi occupation of Rome, the situation of the Segre family was worsened.

The Swedish Institute

in the years 1943-1944

Until June 1943, the activities of the Swedish Institute had continued almost undisturbed. Following the events of the summer and the subsequent German occupation, most of the Swedes left Rome and Sjöqvist remained at the Institute with his wife Gurli, the two scholarship holders and assistants Erland Billig and John Rohnström and the secretary Ragnhild Collijn-Billig. The most difficult period was between September 1943 and June 1944. Sjöqvist wrote in 1945:

«One day we found ourselves without gas, electricity, means of transport, toothbrushes and shoelaces; and if the Swedish legation had not organised the sending of necessities from Sweden so adeptly, the approximately 60 members of the Swedish community would have been without food for periods. Fortunately, the Institute building had not suffered significant damages apart from the tiles that had been hit by shrapnel during the four major bombardments of Rome».

The arrest of the

Segre family

Testimonies to the reconstruction of the events of 5 April 1944 are those of Erik Sjöqvist himself in an article in the Swedish daily Svenska Dagbladet on 6 September 1945, of the two scholarship holders Erland Billig and John Rohnström who left handwritten accounts, and finally of Giovanni Pugliese Carratelli who collected the testimony of Filippo Magi, assistant at the General Directorate of the Vatican Museums and a friend of Segre’s.

Already in early 1944, the Segre family began to leave the Institute for short walks in the Villa Borghese area.

On 5 April 1944 they left the Institute on their way to Prati, to retrieve some personal belongings from their flat, or, according to another version, for a walk in the company of Magi; on the way they were recognised and arrested by two policemen of the Italian Social Republic and taken to the Prati police station.

John Rohnström recounts that he accompanied Sjöqvist at dawn to the police station, where they could only leave some clothes. Sjöqvist asked the police commissioner who was holding them in custody until the Germans arrived, to at least keep an eye on the person who had betrayed them. He was told not to worry and that the person would not get away with it.

Giovanni Battista Montini, then substitute of the Vatican Secretariat of State (the future Pope Paul VI) was immediately informed but could not be of any help as already on 6 April the Segre family was handed over to the Germans and imprisoned at Regina Coeli. In the following days, several individuals, urged by Sjöqvist, appealed to the Secretariat of State. Sjöqvist obtained an audience with Pius XII, who, however, did not intervene; he also turned to the German Ambassador to the Holy See Ernst von Weizsäcker, who had assisted him on other occasions, but this time he could not be of any help. Montini himself spoke with von Weizsäcker on 17 April, but already on 10 April the Segre family had left the prison to be taken to the Fossoli camp near Carpi.

The deportation

«On 16 May 1944 we left Fossoli for Poland, and we travelled together in the cattle wagons until the last day of the journey, that is 22 May, we arrived at Auschwitz Birkenau. From here we were divided up, that is, the women with the children on one side with the old men, the men on the other, and we girls, that is seventy-three, were put on another side, and so there was not even time to say goodbye to each other, only this one word was said between us: “Courage, tomorrow we will meet again”. From here I could see Mr Mario crying his eyes out because he had been separated from his family and he was lined up in a row of five, together with the elderly people and taken away without knowing where. And then I saw his wife and child being taken away together with the elderly women and many children, and the last to be taken away were us, who, of 700 who left Fossoli, after this division were seventy-five of the youngest girls. The next morning many of our friends asked some of the supervisors where we could find the women with the children, and what an atrocious sight it was that they had all been passed to the gas chambers and then to the crematorium and unfortunately died on the same day, that is on 23 May, in the night».

The stumbling stones and the legacy of Mario Segre

Mario Segre, always faithful to his scientific mission, worked until the very end. His brother Umberto (1908-1969), an anti-fascist intellectual and philosopher, the only survivor of the family, devoted himself since 1945 to have his brother’s works published, entrusting the editing to Gaetano De Sanctis and Giovanni Pugliese Carratelli.

Segre’s working materials left at the Swedish Institute – manuscripts, books, abstracts and the typewriter with the Greek characters – were given by Sjöqvist to these scholars. Posthumous works on the inscriptions of the islands of Kalymnos, Kamyros and Kos, whose scientific value is still today very high, were published in 1952 (Tituli Calymnii and Tituli Camirenses) and 1993 (Iscrizioni di Cos).

The stumbling stones (Stolpersteine) created by Gunter Demnig and installed in front of the Institute on 11 January 2017, recall the tragic fate of Mario, Noemi and Marco and remain as a constant reminder for all of us.

Credits

Text by: Astrid Capoferro and Federica Lucci

Graphics and development by Emme. Bi. Soft s.r.l.

Special thanks to Ingrid Edlund-Berry

Bibliography

– ”Intervju med Erik Sjöqvist”, Svenska Dagbladet, 6 september 1945.

– A. Gauffin, ”Ett besök i Svenska Institutet i Rom maj 1946”, Ord och Bild 55, 1946, pp. 401-410.

– C. Nylander, ”L’Istituto Svedese di Studi Classici a Roma”, in P. Vian (a cura di), Speculum mundi. Roma centro internazionale di ricerche umanistiche, Roma 1993, pp. 504-507.

– R. Bottoni, “Note per un profilo biografico di Mario Segre”, in D. Bonetti, R. Bottoni (a cura di), Ricordo di Mario Segre epigrafista e insegnante. Atti della giornata in memoria di Mario Segre e della sua famiglia (Milano, Liceo-Ginnasio G. Carducci 23 maggio 1994), Milano 1995, pp. 25-48.

– M. Barbanera, L’archeologia degli italiani, Roma 1998, pp. 150-152.

– B. Santillo Frizell, “1903-2003. Due centenari all’Istituto svedese: Erik Sjöqvist e Gösta Säflund”, Annuario. Unione Internazionale degli Istituti di Archeologia, Storia e Storia dell’Arte in Roma 45 (2003-2004), 2003, pp. 165-175.

– I. Edlund-Berry, “Erik Sjöqvist: archeologo svedese e ricercatore internazionale alla Princeton University”, Annuario. Unione Internazionale degli Istituti di Archeologia, Storia e Storia dell’Arte in Roma 45 (2003-2004), 2003, pp. 173-185.

– M. Barbanera, Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli: biografia ed epistolario di un grande archeologo, Milano 2003, pp. 217-221.

– M. Segre, Pausania come fonte storica; con un’appendice sulle fonti storiche di Pausania per l’età ellenistica, Roma 2004.

-G. Pugliese Carratelli, “Ricordo di Mario Segre (Torino 1904 – Auschwitz 1944)”, Bollettino d’arte 90, 2005, fasc. 133-134, pp. 1-2.

-F. Berlinzani, “L’opera di Mario Segre: da Pausania alla passione epigrafica”, Bollettino d’arte 90, 2005, fasc. 133-134, pp. 3-8.

-A. Russi, Silvio Accame, San Severo 2006, pp. 87-90.

– F. Whitling, The Western Way: Academic Diplomacy. Foreign academies and the Swedish Institute in Rome, 1935-1953, Florence 2010, pp. 236-243.

– E. Billig, R. Billig, F. Whitling, Dies Academicus: Svenska institutet i Rom 1925-50, Stockholm 2015, p. 192.

-N. Badoud, “Tre pietre d’inciampo”, La Parola del passato 77, 2017, pp. 7-10.

– F. Whitling, Western Ways: Foreign Schools in Rome and Athens, Berlin 2019, pp. 158-159.

– E. Bianchi, “Tra l’Italia e l’Egeo: Mario Segre al tempo delle leggi razziali (1938-1940)”, in A. Pagliara (a cura di), Antichistica italiana e leggi razziali. Atti del Convegno in occasione dell’ottantesimo anniversario del Regio Decreto Legge n. 1779 (Università di Parma, 28 novembre 2018), Parma 2020, pp. 125-141.

– F. Melotto, Un antichista di fronte alle leggi razziali: Mario Segre 1904-1944, Roma 2022.

– F. Melotto, “”Ritengo che sia mio dovere verso la scienza, e verso la scienza italiana in particolar modo”. Mario Segre, un antichista ebreo nel Dodecaneso dopo il 1938”, in E. Bianchi (a cura di), Antichisti ebrei a Rodi e nel Dodecaneso italiano, Napoli 2023, pp. 335-372.

– A. Amico, “La pubblicazione dei Tituli Calymnii di Mario Segre”, in E. Bianchi (a cura di), Antichisti ebrei a Rodi e nel Dodecaneso italiano, Napoli 2023, pp. 373-389.

– A. Mastino, “Introduzione. Epigraphica a 80 anni dalla uccisione di Mario Segre”, Epigraphica 85, 2023, pp. 9-13.

– E. Bianchi (a cura di), Mario Segre: i percorsi di ricerca di un antichista sotto il fascismo, Roma 2024.